Daniel Webster was one of the greatest orator-politicians in the history of the United States. A relentless defender of the American Union, he dedicated much of his political career to its preservation in the face of those who would tear it apart over sectional interests. Though he sought the presidency many times, and served twice as secretary of state, his most lasting achievements were in the United States Senate, where his oratory inspired Unionists like Abraham Lincoln and elevated the upper chamber to the most important forum in the country.

Webster was born in 1782 in Salisbury, New Hampshire, the son of Ebenezer Webster, a farmer and French and Indian War veteran, and his second wife, Abigail. He was the second youngest of eight children between Ebenezer’s two marriages.

He attended Phillips Exeter Academy in 1796 and Dartmouth College in 1797. Today, Dartmouth is one of the nation’s premier educational institutions, but its curriculum was rather unimpressive in Webster’s time, and the young man was drawn to the robust culture of literary societies, where his intellect was truly sharpened.

He was admitted to the bar in 1805 in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and soon emerged among the local elite as an effective critic of the Jefferson Administration’s policies toward New England. His 1808 pamphlet, “Considerations on the Embargo Laws,” was a local success. Reflecting New England’s growing skepticism of federal power, he argued that while the federal government had authority to regulate commerce, it had no power to destroy it, which Webster accused Jefferson of doing. Webster was elected to Congress in 1812, where he became a thorn in President James Madison’s side for his unyielding criticisms of Madison’s conduct in diplomacy and war.

The Federalist Party fell apart after the war’s conclusion, tainted by the talk of secession at the Hartford Convention of 1814. But Webster’s reputation remained intact. He left Congress in 1817, moving to Boston where he established a thriving law practice, which included arguing before the Supreme Court. He was a litigant in Dartmouth College v. Woodward as well as McCulloch v. Maryland, where he advocated strongly for both property rights and federal power.

Webster returned to the House in 1823. The Federalist Party was finished as a political party, and Webster fell in with the New England branch of the Jeffersonians, supporting John Quincy Adams for President. Though Webster had been a skeptic of both the Bank of the United States and protective tariffs in the 1810s, his views evolved to fit the growing economic diversification of his region, which was transitioning from shipping into textile manufacturing. He entered the Senate in 1827, where he would serve for 19 of the next 23 years.

Webster really begins to earn his place in the history books in 1830. South Carolina, led by Vice President John C. Calhoun and Senator Robert Hayne, had embraced the doctrine of nullification, or the idea that states could nullify federal laws that it deemed unconstitutional. The Palmetto State faced economic hardship under the protective tariffs of the 1820s, and believed they were unconstitutional.

Simultaneous to this constitutional objection, Calhoun and Hayne were searching for potential alliances to blunt the tariff, and set their eyes upon the west. Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri believed that New England had been complicating the sale of western lands to stop outmigration and thus keep the price of labor low. Hayne, seeking out a cheap land/low tariff alliance, gave a speech on January 19, 1830 arguing for limited power over land sales. Webster responded by defending the power of the federal government, which prompted a counter-attack from Hayne on New England’s opposition to the War of 1812, and a defense of Calhounian nullification.

On January 26 and 27th, Webster offered what has been remembered as the “Second Reply to Hayne,” a thoroughgoing and relentless dismantling of the doctrine of nullification that utilized all the rhetorical skills that Webster had developed over the last 25 years. The entire speech is quotable, but the last lines are some of the most memorable ever uttered in the history of the United States:

While the Union lasts, we have high, exciting, gratifying prospects spread out before us, for us and our children. Beyond that I seek not to penetrate the veil. God grant that in my day, at least, that curtain may not rise! God grant that on my vision never may be opened what lies behind! When my eyes shall be turned to behold for the last time the sun in heaven, may I not see him shining on the broken and dishonored fragments of a once glorious Union; on states dissevered, discordant, belligerent; on a land rent with civil feuds, or drenched, it may be, in fraternal blood! Let their last feeble and lingering glance rather behold the gorgeous ensign of the republic, now known and honored throughout the earth, still full high advanced, its arms and trophies streaming in their original lustre, not a stripe erased or polluted, nor a single star obscured, bearing for its motto, no such miserable interrogatory as “What is all this worth?” nor those other words of delusion and folly, “Liberty first and Union afterwards”; but everywhere, spread all over in characters of living light, blazing on all its ample folds, as they float over the sea and over the land, and in every wind under the whole heavens, that other sentiment, dear to every true American heart-Liberty and Union, now and forever, one and inseparable!

Tens of thousands of copies of the speech were printed. And while Webster lost the immediate debate — as the Democratic Party would soon embrace expansion and lower tariffs — his speech signaled the maturation of a pro-Unionist movement, intent on holding the country together despite the growing sectional tensions.

Henry Clay and Webster would be its champions. The two men, once divided in the Madisonian Era, now joined as allied members of the Whig Party in the Senate, supporting economic nationalism and looking to defend the Union. Along with Calhoun, the three would become known as the “triumvirate.” It was not because they were allies. On matters of federal power Calhoun stood against Clay and Webster. It was not because they were in power — all three men tried and failed to acquire the presidency. It was because the three of them, through their eloquence and intelligence on the floor of the Senate, gave voice to the national debate over the nature of the Union itself.

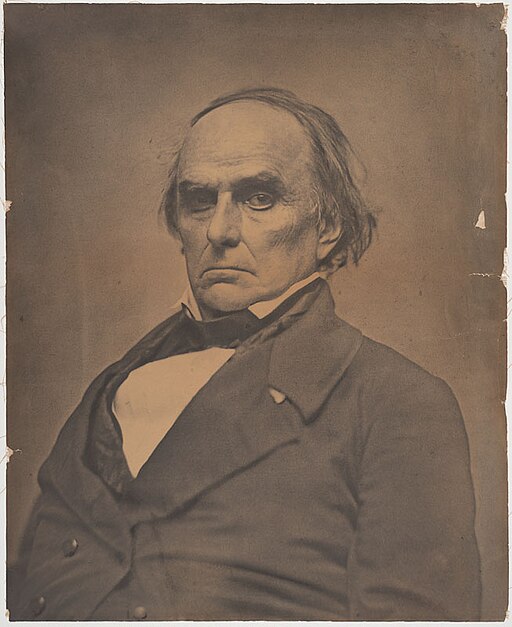

Webster became known as the “God-like Daniel.” His dark skin, arched eyebrows, and deep-set eyes combined with his deep voice and soaring rhetoric to make him seem almost superhuman. Yet his sublime public persona contrasted sharply with his personal life, where his excessive spending habits induced him frequently to default on loans, even to friends. The fact that he was a solid supporter of the economic interests of New England gave the appearance of corruption.

Webster left the Senate to serve as secretary of state under John Tyler from 1841 to 1843, even as the nation’s first accidental president clashed with Whigs in Congress. He returned to the Senate in 1845, where he opposed the Polk Administration’s territorial expansionism and especially its initiation of the Mexican-American War. The climax of Webster’s senatorial career was the fight over the Compromise of 1850. When California requested admission as a free state, southerners balked and another crisis over the Union emerged. Clay helped design a deal in which the admission of California would be paired with a tough fugitive slave law to mollify the South, combined with various other measures to create a transregional coalition.

Clay’s “Compromise of 1850,” as it was known was incredibly divisive and most Northern Whigs opposed it. Ultimately, the package had to be passed by stitching together a coalition of Northern Democrats and Southern Whigs. But Webster was staunch in his support. Defying his region, he spoke in favor of the deal on March 7, 1850. “Mr. President,” he began,” I wish to speak today, not as a Massachusetts man, nor as a Northern man, but as an American, and a member of the Senate of the United States.…I speak for the preservation of the Union. Hear me for my cause.”

Unlike his response to Hayne more than 20 years ago, this was a political death knell. Webster was harshly denounced in Massachusetts. Henry David Thoreau, in a speech entitled “Slavery in Massachusetts,” given in 1854 after Webster’s death, denounced the Fugitive Slave Act and Webster himself in harsh terms:

I hear a good deal said about trampling this law under foot. Why, one need not go out of his way to do that. This law rises not to the level of the head or the reason; its natural habitat is in the dirt. It was born and bred, and has its life, only in the dust and mire, on a level with the feet; and he who walks with freedom, and does not with Hindoo mercy avoid treading on every venomous reptile, will inevitably tread on it, and so trample it under foot — and Webster, its maker, with it, like the dirt-bug and its ball.

Webster’s reputation in New England never recovered. Millard Fillmore named him Secretary of State in 1850. Webster took the post hoping to restore his reputation in preparation for another run at the presidency (he had sought it in 1836 and 1848). But the Whigs nominated Winfield Scott, a hero of the War of 1812 and Mexican-American War. Webster died that October, at the age of 70.

Webster’s Unionism fell out of vogue in the 1850s, as North and South polarized. But Lincoln’s unyielding quest to save the Union was premised on the very ideas “Black Dan” had articulated in his opposition to Robert Hayne and his support of the Compromise of 1850. Moreover, Lincoln’s pragmatism in his second inaugural, “With malice toward none, with charity for all,” further reflects Webster’s spirit of moderation to hold the nation together. That view was not especially popular in New England in 1850, but it certainly left a profound impact on the railsplitter from Springfield.

Webster also helped establish the Senate as the preeminent forensic venue in the United States. It was because of him, along with Clay and Calhoun, that people looked to the Senate as the site where the great issues of the day were debated, and compromise forged.

Today, Senate debates are relatively rare, and the rhetoric in the chamber pales in comparison to Webster’s stirring oratory. Yet Americans would be wise to revisit Webster’s speeches for they are a reminder that Congress can be a forum where the public’s views are given expression in a reasoned, eloquent, and uplifting fashion.

Jay Cost is the Gerald R. Ford Senior Nonresident Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. He is the author of five books, most recently Democracy or Republic? The People and the Constitution (AEI Press, 2023).

Stay in the know about our news and events.