Ahead of the 2026 midterm elections, the parties are playing hardball. Texas Republicans have convened a special session of their legislature to redraw the state’s map of congressional districts, with the intention of eliminating several Democratic seats. Similar Republican efforts appear underway in states like Ohio and Missouri. California Governor Gavin Newsom has responded by threatening to change the state’s laws so that Golden State Democrats can eliminate Republican seats.

This is known as “gerrymandering,” and it is normally a battle fought at the beginning of the decade. The Constitution requires the decennial census, after which House districts are apportioned according to population.

States that have more than one House seat then have to decide where the lines between districts are drawn. When this “redistricting” becomes a blatantly partisan exercise, it is known as gerrymandering.

It is unusual for the two parties to be fighting about gerrymander in the middle of a decade, though not unprecedented. Republicans redrew the Texas map in 2003 after the party gained control of the legislature. Democrats redrew the New York map last year after the state court ruled that the original, nonpartisan map could be replaced. The fight for every possible House seat is a consequence of the closely contested nature of the House. Neither party wants to leave anything to chance.

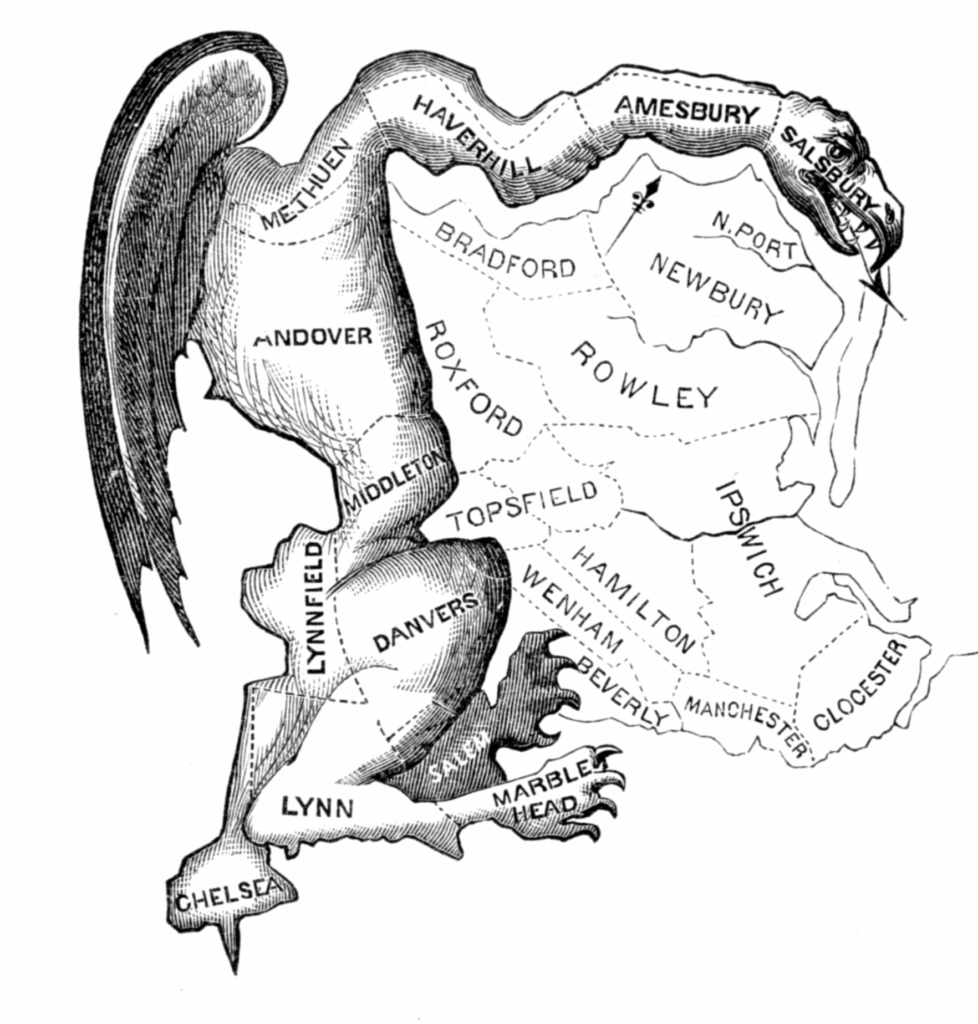

Gerrymandering is a very old practice — the word itself is the tell. The name comes from Elbridge Gerry, the Jeffersonian governor of Massachusetts who in 1812 approved a map of districts that packed Federalists into several districts. The Boston Gazette described one of the districts as a “gerrymander” because it looked like a salamander. But it goes back farther even than that. In 1788 Patrick Henry, the leader of the Anti-Federalists in the Virginia House of Delegates, sought to prevent James Madison from being elected to the First Congress. He had Madison’s Fifth District, which included his home county of Orange, drawn to include counties with what Henry thought were Anti-Federalists leanings. James Monroe ran against Madison, who still managed to win, but no thanks to Henry.

The strategies pursued by Gerry and Henry are still the main styles of gerrymandering today — packing and cracking. Packing a district, as Gerry did, involves placing as many opposing partisans as possible into as few districts as possible. The result is a safe district or two for the other party, but then your side gets to have as many districts as possible. A good example of a packed district is Illinois’s 20th Congressional District, which zigs and zags across the center of the state to concentrate rural Republicans into the district. Cracking, on the other hand, is a strategy to break local partisans across multiple districts, thereby diluting their influence in elections. A good example of this is the treatment of Salt Lake, Utah. A reliably Democratic community, its voters are split across four districts, thereby generating a state delegation of four Republicans.

Gerrymandering is one of the purest expressions of raw political power in the United States. It is a “hack” of republican government. Yes, every vote counts — but how should they count? Both sides have done it since the very beginning of the republic because doing it increases their membership and power in the House of Representatives.

The Constitution has nothing directly to say about the practice. It grants the power to set the time, place, and manner of elections to the state legislatures, but gives Congress the power to alter state laws as it sees fit. In Rucho v. Common Cause (2018), the Supreme Court ruled that partisan gerrymandering is not justiciable because it is a political matter. The Court has involved itself in racial gerrymandering, or the practice of drawing districts that favor or disfavor one race over another. That is because the 1982 amendments to the Voting Rights Act (VRA) prohibits electoral rules that have the effect of discrimination. The Court has interpreted that to mean that states are sometimes compelled to draw minority-majority districts, where a racial or ethnic minority constitutes a majority of the district (as the Fifth Circuit required Louisiana to do in 2023). On the other hand, the Court has sometimes ruled that states have gone too far, packing minority voters into districts that reflect no geographical community (as in the old North Carolina 12th District). The Court has been struggling to establish clear standards on racial gerrymandering for the last 30 years, and a major VRA case is once again on the docket for the next Court term.

Absent federal oversight, gerrymandering is a struggle that occurs exclusively in the states, according to state rules. Some states — like Arizona and California — have independent redistricting commissions, nonpartisan entities whose purpose is to depoliticize the drawing of district lines. New York and Virginia employ a hybrid system, where a non-partisan commission makes recommendations to the state government. Most states draw their lines through the political process, usually with the state legislature drawing the lines and the governor having the power to issue a veto. It is among these states where, if one party has the governing trifecta (the state house, state senate, and governor’s mansion), it can draw highly partisan lines. [KK1] Notable examples of aggressive Democratic gerrymanders include Maryland and Illinois, where Republican voters are effectively disenfranchised. On the Republican side, Tennessee and North Carolina are states where the GOP has leveraged its statewide advantage to sheer domination of the congressional delegations.

One of the issues with gerrymandering is that there is no agreement on what constitutes a fair district. Obvious gerrymanders like Illinois notwithstanding, the issue can get muddled very quickly. Should it be compactly drawn, without crossing political boundaries unless necessary? Should it reflect communities of interest, like cities, suburbs, or rural areas? Should it strive for partisan balance within the district, creating as many competitive seats as possible? Should districts aggregate to reflect the partisan balance of the state?

There is a case to be made for all of these standards, but they are often in conflict. For instance, the map of Florida’s districts is reasonably compact and generally reflects communities of interest. But because Democratic voters are concentrated in urban communities like Miami, the result is a decisive Republican advantage. On the other hand, creating a map that reflects a statewide partisan balance often requires crisscrossing many political boundaries, in an effort to distribute urban Democrats across multiple districts. Moreover, seemingly nonpartisan processes as those in California and New Jersey have produced maps that favor Democrats over Republicans, well above their vote totals in the state.

If one were to compare old congressional maps to today’s, you might think gerrymandering has gotten worse. But the reality is more complicated. In a series of cases —Baker v. Carr, (1962), Reynolds v. Sims (1963) andWesberry v. Sanders (1964)—, the Warren Court ruled that the 14th Amendment required the standard of “one man, one vote.” Districts had to be roughly equal in population. Prior to that, representation systematically favored rural communities over urban ones. So, even if old maps look fair, they were actually partial to some voters over others.

Still, there is no doubt that redistricting has become more sophisticated. Computers fed granular data on voting patterns can draw precise maps that maximize partisan advantages — a tool that Gerry and Henry simply lacked in the days of the early republic. Additionally, the growing size of House districts has created more opportunities for ambitious gerrymanders. With nearly 750,000 people in the average district, there are a number of ways to slice and dice partisan voters.

That points to the best way to minimize gerrymanders. Top-down solutions do not admit of agreed-upon standards, and nonpartisan commissions often produce partisan results. Trying to shift the entire country to multi-member districts chosen by fusion voting or preferential voting seems politically impossible. Adding more seats in the House of Representatives, however, would have positive effects: districts would shrink, more communities would have direct representation, and the opportunities for gerrymandering would decrease. It would not solve the problem — but then again, if history has told us anything, it is that gerrymandering is a fact of political life.

Jay Cost is the Gerald R. Ford Senior Nonresident Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. He is the author of five books, most recently Democracy or Republic? The People and the Constitution (AEI Press, 2023).

Stay in the know about our news and events.