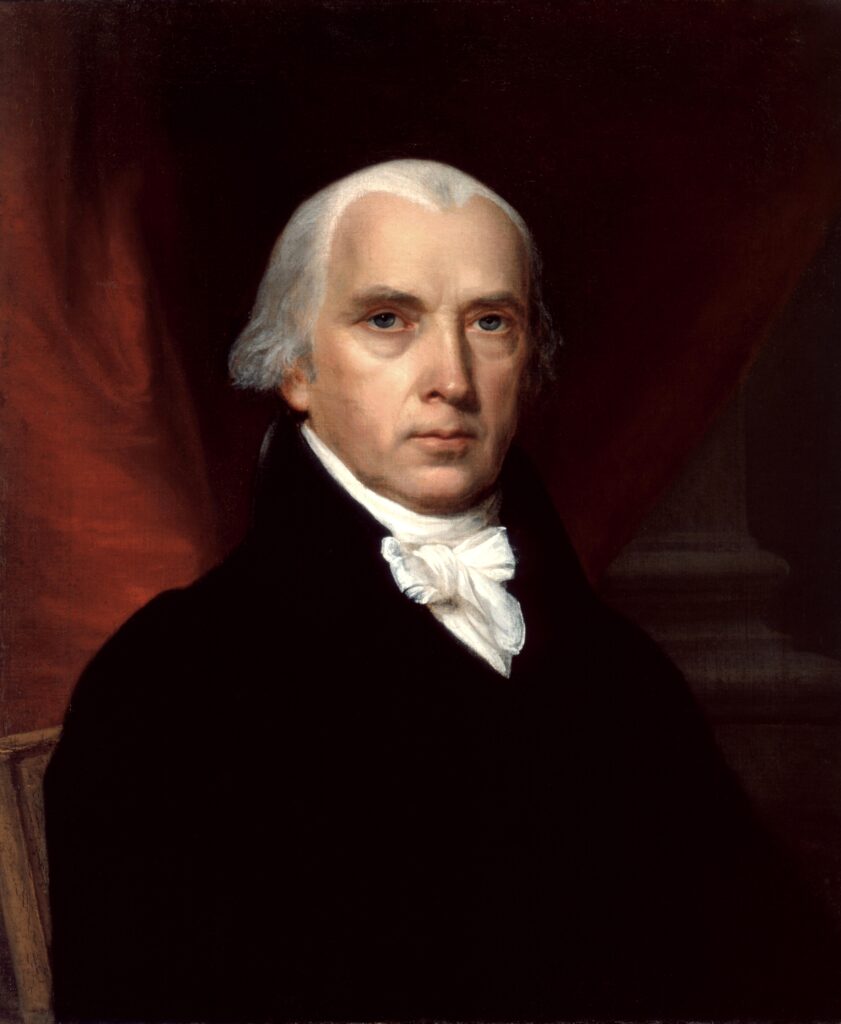

In his 1836 eulogy of James Madison, John Quincy Adams called the late president the “Father of the Constitution.” It was not the first time Madison was called that; Jared Ingersoll toasted the former president with that name about a decade earlier. Still, Adams’s use of the sobriquet permanently inscribed it in the historical memory.

And with good reason. Nobody worked harder behind the scenes than Madison to put together the Constitutional Convention. He devised a plan of government, known as the “Virginia Plan,” that served as a framework from which the founders built the Constitution. He gave more speeches than almost anybody at the Convention. He defended it brilliantly in dozens of Federalist essays. He authored of the Bill of Rights.

It is that last item on his list of constitutional achievements that points to another, often overlooked aspect of Madison’s career. The Bill of Rights was not the creation of the Constitutional Convention, but rather of Congress. This collection of 10 amendments came to be due to the efforts of Madison, who for all intents and purposes the first majority leader of the House.

To be clear, Madison never held that title in the same way that Rep. Steve Scalise (R-LA) currently does. The title did not exist when Congress first opened its doors in the spring of 1789. Almost nothing did. Nowadays, a new member of Congress must learn all manner of rules and procedures to be an effective member. There is even a mandatory orientation session they all are supposed to take. But when the House gaveled into session in April 1789 there were no rules beyond those briefly laid out in the Constitution. There was no organization beyond the speaker, whose role was completely undefined in the Constitution. It was into this vacuum stepped Madison.

That he even managed to get into Congress was somewhat remarkable. Madison had been a leading Federalist in Virginia, and was instrumental in securing ratification at the Virginia ratifying convention. But Anti-Federalists, under the leadership of Patrick Henry, were still in charge of the Virginia legislature. Henry had lost the fight over ratification but was unbowed. Intent on continuing the battle against consolidated government in the Congress, he ensured that two Anti-Federalists – Richard Henry Lee and William Grayson – were chosen to be the Old Dominion’s first senators. Madison finished third in the balloting, which was fine by him – he preferred going into the House, anyway. But Henry successfully drew Virginia’s Fifth District to include Madison’s home county of Orange with other counties that had elected Anti-Federalists. Henry also prevailed upon James Monroe to run for the seat. Madison was forced to return to Virginia from New York City (where he had been serving as a delegate to the soon-to-defunct Continental Congress) to campaign. The contest was gentlemanly and polite – Madison and Monroe campaigned together and remained friends. (You can still visit the Hebron Lutheran Church in Madison, Virginia to see where the two campaign; late in life Madison reported he suffered frostbite from the trip.) Madison prevailed in the contest by a margin of 57 percent to 43 percent, an indication that, for how heated the fight over the Constitution had been, many Anti-Federalists had accepted the document and were ready to move on.

Today, we think of the Senate as being more prestigious than the House. Arguably, that was not the case in 1789. The differences in number were not all that dramatic, 59 House members at the start of the First Congress compared 22 senators (as both North Carolina and Rhode Island had not yet ratified). Most legislation – and all revenue-raising bills – originated in the House, with the Senate primarily reviewing and amending the work of the lower chamber. And House debates were open to the public, while the Senate was private, making the House the center of the national conversation about politics.

Madison rose to the top of the congressional heap thanks to his extensive experience in legislative assemblies, which he had been serving in since 1776, as well as his almost superhuman work ethic. In doing so, he took the lead in three essential projects for the new nation – the impost, the establishment of the State Department, and the Bill of Rights.

To contemporary eyes, the impost of 1789 may seem the least interesting legislation of the First Congress, but it was the most essential in its day. The Continental Congress had lacked the power to tax, and the national government had fallen deeply into arrears with foreign and domestic creditors. Securing a source of public revenue was the first order of business. Madison played an integral role in constructing the nation’s first tax law, in two respects. First, his experience in the Continental Congress trying to get the impost of 1781 enacted had provided him an education in the economics of the early republic. Second, the political theory he developed in defense of the Constitution was useful in guiding the legislation to final passage. Federalist 10 is still read today as the great Madisonian treatise on factional rivalries in the early republic. Those factions came out in force to ensure that their regional interests were well served in the new impost, and Madison positioned himself as congressional mediator, making sure that the final package did not burden one group to harshly or reward another too generously.

Madison also played a key role in establishing the State Department, a matter that – while seemingly anodyne on the surface – revealed a knotty constitutional question upon closer examination. The Constitution gave the president the power, with advice and consent from the Senate, to choose executive officers. But what about the power to remove them? The founding document was silent, and as the House debated the details of the State Department, it became clear that Congress could not create the executive departments without taking a position on this subject. Some, like Roger Sherman of Connecticut, argued that the power to remove officials belongs ultimately to Congress. As the author of the laws creating the departments, Congress had the power to establish the procedures for removal. Madison, on the other hand, disagreed. Worried about the legislature interfering in the domain of the president, he asserted that the removal power was inextricably link to the enforcement of the laws, which was vested in the president alone. How could the chief magistrate “take care that the laws be faithfully executed” if he cannot remove officials that are, in his judgment, failing to do precisely that? Ultimately, Madison’s argument carried the day. The final law created procedures to replace the secretary whenever he “shall be removed from office by the President of the United States” – a careful construction, as it presumes that the power belongs to the president under the Constitution, rather than any law of Congress.

The Bill of Rights was the most significant achievement of that first meeting of Congress, but Madison had to convince the House to consider it at all. It was the Anti-Federalists who had called for a bill of rights to the Constitution. Most Federalists agreed with Alexander Hamilton in Federalist 84 that a bill of rights would be redundant if not dangerous. “For why declare that things shall not be done which there is no power to do?” While several states had ratified the Constitution with the expectation that changes be made to it later, the Federalists had dominated the elections to Congress, and these members were not inclined to that view. They objected that there was more important work to be done – establishing the courts and the executive departments – or that the Constitution needed a fair test before it was amended.

Madison himself had not supported a bill of rights initially. He doubted its efficacy, telling Thomas Jefferson, “Repeated violations of these parchment barriers have been committed by overbearing majorities in every State.” Moreover, he worried that the Anti-Federalist call for revising the Constitution was a sneaky way of undermining the whole endeavor. If states began demanding one change after another, the project would fall apart. But after ratification, he changed his position. There was no longer a threat of undoing the Constitution, and a well-designed bill of rights could have a beneficial effect on the nation, orienting the country toward its fundamental liberties and suggesting ways for states to revise their own bills of rights. Given widespread demand for an enumerated list of rights, Madison also felt compelled by public opinion, which he would later write is the “true sovereign in every free government.” Without much interest from the rest of the House, it was Madison who compiled the Bill of Rights – drawn from classic statements of English liberty, like the Magna Carta and the English Bill of Rights, and informed by the recommendations of the state ratifying conventions. For the most part, Congress adopted his proposed list and made few changes.

All in all, Madison was the essential man of the first meeting of Congress. Perhaps the best illustration of his influence was George Washington’s inaugural address. The president had his secretary, David Humphreys, write an early draft of it, but unsatisfied with the result, he turned to Madison in February 1789, who was traveling from his home in the Virginia Piedmont to New York City. Madison served as Washington’s ghostwriter, refining the points the president which to make into the polished draft that became part of history. A few months later, the House appointed a select committee to write an official response to the inaugural, with Madison serving as chair. And so it was that communication between the executive and the legislature was essentially Madison corresponding with himself!

Madison’s time as leader of the Federalists in Congress was short lived. The first session of Congress ended in September 1789. When the second session began in January 1790, Alexander Hamilton submitted the Report on Public Credit, the first of several proposals that would transform American public finance and the shape of its politics. Hamilton would become de facto prime minister of the Washington Administration, while Madison would oppose him, in so doing planting the seeds of American partisanship. Madisonian opposition in the House would, in short order, blossom into a broad-based political coalition known at the time as the Republican Party (today referred to as the Democratic-Republican Party). Madison would win election to the second and third Congresses, but retire in 1797 to his Montpelier homestead, returning to government in 1801 as the secretary of state.

The period of Madison’s domination of the House was quite brief, from April to September 1789. But it constitutes one of the most significant accomplishments of his career in government. Not only was he essential in enacting important pieces of legislation, he helped establish the way the House would do business and prove to the nation that Congress could accomplish the tasks the Constitution laid out for it.

Jay Cost is the Gerald R. Ford Senior Nonresident Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. He is the author of five books, most recently Democracy or Republic? The People and the Constitution (AEI Press, 2023).

Stay in the know about our news and events.