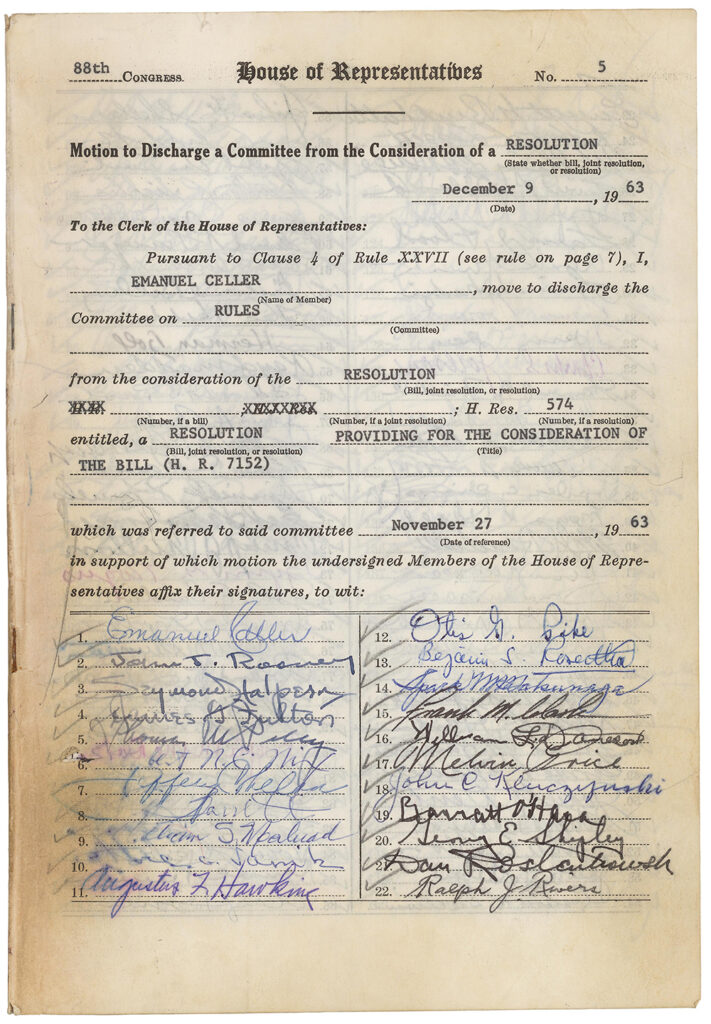

Discharge Petition to Move the Civil Rights Bill Out of the Rules Committee, December 12, 1963. This petition failed to gain sufficient signatures. Source: National Archives.

In most circumstances, the Speaker of the House and the Committee on Rules (Rules Committee) effectively control what bills are considered on the floor of the House of Representatives. Therefore, rank-and-file members seeking to advance their favored bills attempt to work through partisan leaders, either to secure consideration for their bill or find another bill likely to advance, to which they can attach their provisions. Various mechanisms do exist to circumvent the Rules Committee and the Speaker, however, allowing a majority of members to advance a piece of legislation even if the chamber’s leaders prefer that it were not brought up for a vote.

Perhaps the most important of these formal mechanisms is the discharge motion (Rule XV, Clause 2), which provides a means for Members to bring to the floor for consideration a public bill or resolution that has been referred to committee but not reported. Such motions are only in order once a member has collected the signatures of 218 members of the House, and after a prescribed delay of 30 legislative days has elapsed. Both of these limitations make discharge petitions unwieldy and therefore rare, but the possibility of successful discharge petitions nevertheless significantly shapes power dynamics in the House.

Discharge petitions can work in two different ways: by discharging a committee of jurisdiction of a bill that has been referred to it, or by discharging from the Rules Committee a resolution proposing a special order that will provide for consideration of an underlying bill. Because the first method still leaves members with the problem of calling up the bill for floor consideration, the second method has become more prevalent in recent years.

This memorandum first explicates the precise mechanics of how this type of discharge petition operates and explains three prominent attempts at discharge petitions made in the 118th Congress. It then considers the last two petitions to reach 218 signatures, in 2002 and 2015; offers a historical account of how the discharge petition has changed over more than a century in the House; and finishes with a brief inventory of ways that the discharge petition could be reformed.

Mechanics of Discharging a Resolution from the Rules Committee

Using a discharge petition to discharge a resolution containing a special order from the Rules Committee is the most direct way of seizing control of the agenda and dictating the terms of debate on an underlying bill. It has therefore become the favored method of discharge petitioners, who must go through each of the following steps (drawn from Congressional Research Service, updated 2015 and 2023):

While basic discharge petitions—those filed directly on a substantive bill—are moot if the committee of jurisdiction reports the measure before the motion to discharge is made on the floor, discharge petitions on special rules remain valid even if the committee of jurisdiction reports the measure in the mandated layover period. The Rules Committee can short-circuit the discharge petition and regain control by reporting the rule, or by reporting another special order to debate the underlying bill, but those actions would at least still provide paths to floor consideration of the bill.

Discharge Petitions in the 118th Congress

The narrow Republican majority in the 118th House has been unusually internally divided, leading to frequent questions about the majority party’s ability to control the agenda. At various times, the House Freedom Caucus (which brings together the conference’s most hard-right members) has threatened to block legislation from coming to the floor—including by threatening to eject the Speaker of the House (which they did for the first time in history in October 2023). Since Democrats control both the Senate and the White House, at various times House Democrats have looked to the discharge petition as a way of bringing important legislation directly to the floor. To this point, Speakers Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) and Mike Johnson (R-LA) have avoided any petitions by eventually bringing desired legislation up for a vote. Nevertheless, it is instructive to see the role that the discharge petition has played in shaping the interactions of the majority leadership, moderate members of the majority party, and the minority party.

The first episode in which members considered employing the discharge petition was related to the debt ceiling. In January 2023, the U.S. Treasury’s outstanding debt reached its statutorily defined limit, leading the country to adopt a well-worn set of accounting maneuvers known as “extraordinary measures,” which would give until roughly June to negotiate a change to the statutory limit. Having retaken the House majority in the 2022 midterms, Republicans felt they could make hefty demands of the Biden administration. Some GOP members, including many from the Freedom Caucus, felt that Republicans would be betraying their supporters if they did anything less than fundamentally overhaul the federal budget.

Faced with what he considered unreasonable and ill-defined demands, President Biden was standoffish; he said that it looked impossible to negotiate with Republican leaders at all, meaning that an alternative path to raising the limit would need to be pursued. The discharge petition was suggested as one of the best options, with the hope that all Democrats and a few centrist Republicans would tee up a vote on a “clean” debt limit raise. Moderate Republicans expressed unyielding opposition to this approach, but some on the Democratic side assumed that their resolve would wilt if a debt limit breach began to look imminent.

The Democrats’ strategy for employing the discharge petition involved discharging a resolution containing a special order from the Rules Committee—as has been typical in recent years. But rather than have the resolution target a well-defined, substantive bill, it instead would have called up a “shell” bill and then replaced its text with a substitute amendment submitted by the ranking minority member of the Ways and Means Committee. In other words, members were invited to sign onto an effort to discharge never having seen the bill in question. In order not to be delayed at a crucial moment, Democratic leaders coordinated to have a bill properly introduced in January, though they did not make this public. Finally, in May, with the deadline bearing down, they publicized their strategy. On May 17, 209 Democrats signed on, and 3 more added their names by May 24. This meant that just 6 Republicans could have effectively bucked their leadership and—assuming they trusted Democrats’ assurances that the substitute amendment would consist only of a clean debt limit increase—helped to avoid default, though the timing by that point would have been dicey. In the event, McCarthy and Biden agreed to a deal on May 27, leading to the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023. The discharge petition was not completed, but its presence surely impacted the negotiations by creating the possibility that moderate Republicans could seize control of the agenda if they believed McCarthy had badly overplayed his hand.

The second episode involving the discharge petition involves the push for a supplemental spending bill that would provide aid to Ukraine, Israel, and Taiwan. On this issue, Republicans are deeply divided, with a significant minority of members skeptical of sending any more aid to Ukraine but most members ultimately supportive. Originally, Speaker Mike Johnson insisted that any foreign aid be coupled with a bill addressing the security situation on America’s southern border, but when a bipartisan group of senators negotiated such a bill, former President Donald Trump came out strongly against it and Johnson quickly followed. That left the Senate to pursue a foreign aid bill without border security. A bipartisan coalition passed a $95 billion bill in February 2024, 70-29.

Johnson and other GOP leaders faced intense opposition to the House taking up that bill. As a result, two discharge petitions were simultaneously started as a way of potentially seizing control of the House floor.

The first of these, Petition No. 9, was the Democrats’ effort, led by the ranking member of the Rules Committee, Jim McGovern (D-MA). As with the debt limit bill, the resolution in question sought to call up a bill but have its substance replaced with a substitute amendment to be introduced by the ranking member, this time of the Appropriations Committee. In this case, Democrats would certainly substitute in the exact bill text that had already passed the Senate, so that House passage would send the bill on directly to the president. On the petition’s first day, it got 169 Democratic signatures, up to 194 a month later. Many progressive Democrats have withheld their support because of the package’s support for Israel. Only one Republican member signed—former Rep. Ken Buck (R-CO), who added his signature before retiring from the House. (Peculiarly, signatures from former members still count toward 218.)

The second petition, Petition No. 10, was started by moderate Republican Brian Fitzpatrick (R-PA). It targeted the same underlying bill as the Democrats’ debt limit discharge petition in 2023, presumably for eligibility purposes. Instead of substituting language to be specified later, though, Fitzpatrick’s resolution would have substituted the text of another bill, H.R. 7372, the Defending Borders, Defending Democracies Act, sponsored by Rep. Jared Golden (D-ME) and cosponsored by a bipartisan group of moderate lawmakers. The bill would force the Biden administration to revert to the “Remain in Mexico” policy in dealing with the flood of asylum-seekers, as well as providing a total of $66 billion for Ukraine, Israel, and Taiwan. When Fitzpatrick introduced his discharge petition on March 12, most of the bill’s cosponsors quickly added their signatures, and a few others did as well. Nevertheless, by the end of March it had only 16 signatures and looked to be stalled out.

In early April 2024, it looked as though the discharge petitions might not be relevant; some thought that Johnson would simply bring up the Senate bill under suspension of the rules, despite the backlash he would face in his conference. But he ultimately shied away from that approach, perhaps because of the threat from Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA) to offer a motion to vacate. Instead, the Speaker feverishly sought a procedural way forward that would satisfy Republicans. He eventually settled on the strategy of breaking the bill up into its component parts, which would allow many GOP members to support Israel funds while rejecting Ukraine. Republican Rules Committee members did not unite around this plan, though, making it unclear whether Johnson could proceed, and at that point talk about the discharge petitions returned in full force—the fact that the Democrats’ Petition No. 9 would need only two dozen additional signatures meant that Republican Ukraine backers could ultimately force the issue, on the Senate’s terms, if they chose to act in unison. The speaker and his allies on the Rules Committee managed to convince Democrats that the aid packages’ best chances were to be teed up by a bipartisan rule, which passed on April 19, 2024. The discharge petition would not be needed, but it had unquestionably created a path that affected negotiations in their last stages.

Two Successful 21st Century Discharge Petitions

Just two discharge petitions have made it to 218 signatures in the 21st century.

The first was on the explosive subject of campaign finance reform. House Republican leaders were staunchly opposed to these efforts, and had no interest in letting these bills be considered on the floor. In the 105th Congress (1997-98), a bill had been successfully discharged and then passed by the House, 252-179. It failed to progress in the Senate. In the 106th Congress (1999-2000), a discharge petition failed to gain enough signatures. But in the 107th Congress, reformers made a renewed push for the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act, better known as McCain-Feingold after its Senate sponsors, but known as Shays-Meehan in the House. Speaker of the House Dennis Hastert (R-IL) and the Rules Committee sought to bring up the bill under a rule that its supporters believed was meant to sabotage the bill, but reform-minded Republicans joined with Democrats to defeat the rule in July 2001. Instead, they introduced a discharge petition on a rule providing for up-or-down consideration of the bill. Their effort was buoyed by the scandal then unfolding as the market-manipulating energy giant Enron collapsed, and they got the necessary signatures in January 2002. Rather than let that clean up-or-down vote take place, however, the Rules Committee countered with a new rule providing for a substitute amendment to be considered. That substitute, and other efforts to alter the bill in ways unwelcome to its champions, failed, and the bill itself went on to pass the House and then Senate.

The episode demonstrates that, while the discharge petition significantly alters the power dynamics between leaders hoping to bottle up a bill and members seeking to pass it, successfully discharging the bill need not be the last move in the game.

The second successful discharge petition came in October 2015, a tumultuous time for the House. Speaker John Boehner (R-OH) had announced his impending retirement at the end of September but had not yet left; meanwhile, a number of difficult fiscal policy questions needed to be resolved. House conservatives strongly opposed reauthorization of the Export-Import Bank, which they said was a prime example of “crony capitalism.” Its authorization had recently lapsed, and conservatives wanted to kill off the institution permanently. Boehner himself was not against the bank, but his presumptive successor, Paul Ryan (R-WI) came out against its renewal, and it appeared that a reauthorization bill would stall. Amidst this chaos, Rep. Stephen Fincher (R-TN) and other Republican supporters of the bank launched a discharge petition and collected all of the necessary 218 signatures in a single day. Their discharged resolution provided for a closed rule, setting up a straight up-or-down vote on reauthorization. It soon got that vote, and easily passed, 313-118 (127-117 among Republicans). In this case, the discharge petition facilitated full-chamber consideration of a popular bill that leaders, for complicated coalition-maintenance reasons, would otherwise have not brought to the floor.

History of Changes to the Discharge Petition Procedure

The Discharge Petition rule dates to the 1910 revolt against Speaker Joseph Gurney Cannon (R-IL). Along with ending his dominance of the Rules Committee, progressive Republicans joined with minority Democrats to create a pathway for calling up a bill that would not depend on the Speaker or Rules Committee. As explained in the Rules Committee’s official history (1983, pp. 118-123) it did not get much use in its early years, largely because Democratic majorities from 1911-1919 acted cohesively through their caucus. In 1924, with Republicans again in control of the House and again experiencing pressure to allow majorities to act independently of leadership, the rule was significantly changed, including by lowering the number of member signatures needed to enable a motion from 218 to 150; stipulating that on the actual discharge vote, only a majority of the quorum present would be needed (rather than a majority of the entire House); and making resolutions (including those containing special orders) eligible to be discharged. Republicans, in possession of a stronger majority after the 1924 election, changed the number back to 218 in 1925. When Democrats retook the House in 1930, they lowered the number to 145, a third of the full House. Finally, in 1932, the discharge petition procedure was successfully used to call up and then pass the soldiers’ bonus bill. With large Democratic majorities in place during the New Deal, the number was raised back to 218 in 1935, and this level has persisted through the present day.

Under this regime, most discharge petition efforts are, of course, unsuccessful. By Sarah Binder’s 2023 count, less than 4 percent of the 638 petitions begun since 1935 got the requisite 218 signatures, and something like 8 percent of bills targeted for discharge were passed by the House. Notably, discharge petitions have often been important factors in intraparty struggles. As Binder points out, discharge petitions initiated by members of the majority party have, historically, been considerably more likely to succeed.

The discharge procedure has undergone one other major change in its history: in 1993, the House decided to change the procedure for publicizing signatures. Prior to that time, signatures were only made public if the threshold (usually 218) was reached. But Rep. James Inhofe (R-OK) took it upon himself to force Members to “back up their public statements with action.” When Inhofe’s Discharge Petition Disclosure Bill was itself “buried” in the Rules Committee, Inhofe began a discharge petition, threatening to release the names of all Members who refused to sign. He made good on his threat, with the Wall Street Journal publishing the names of Members who did not sign onto his discharge petition. After considerable resistance, the scandal-plagued 103rd House finally relented, Inhofe’s petition got its 218th signature, and his resolution passed easily, 384-40. A casual inspection of Binder’s data suggests that successful discharge petitions have become less common since the change. In any case, the dynamics of discharge petitions are undoubtedly somewhat different with names being revealed on a continuous basis.

Options for Reforming the Discharge Petition

If the House wanted to make it easier for a majority of the chamber to assert control of the agenda even when the majority party’s leadership would prefer to suppress a bill, adjusting the parameters of the discharge petition rule would be one of the most straightforward ways of doing so. There would be several obvious options, given the history discussed in the previous section.

The House could:

Philip Wallach is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and author of Why Congress (2023). Priscilla Goh is a former intern at the American Enterprise Institute.

Stay in the know about our news and events.